Introduction: Conflict, Displacement, and Environmental Stress

Sudan’s recent waves of conflict erupted in April 2023, following earlier crises in Darfur, between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), forcing millions to flee their homes. This war is not only a humanitarian catastrophe; as it is an escalating ecological crisis. As reported by the Conflict and Environment Observatory, the fighting has unleashed significant direct and indirect damage on the nation's fragile environment, severely impacting the lives of both urban and rural populations [1]. Key consequences of this devastating conflict include rapidly accelerating deforestation, a steep decline in agricultural output, widespread pollution from damaged industrial and energy infrastructure, crippling power outages, and the near-total breakdown of essential health and sanitation systems [1]. This environmental decay threatens the long-term stability and recovery of the entire country. Understanding these intersecting crises requires more than mere data; it requires meaningful communication that bridges the gap between lived experience and scientific knowledge.

The Climate–Conflict Supply Chain in Sudan

The devastating intersection of climate and conflict is tangibly visible in Darfur’s gold economy [2]. Numerous investigations have documented how revenue from this gold directly and indirectly finances armed groups, including the warring factions. Compounding the violence, the extraction process itself causes severe environmental damage, leading to land degradation, water depletion, and deforestation [3]. This process pollutes vital resources as well as creates new resource disputes, worsening community vulnerability and deepening the cycles of violence. Science communication can help communities understand how their local environmental struggles and resource disputes link to these vast global supply chains, a realisation that is crucial for empowering them with actionable knowledge and agency to demand accountability and safer practices.

Why Communication Fails in Crisis

In the chaos of conflict, there is a fundamental disconnect: scientific information rarely reaches the affected communities in a way they can actually use [4]. When people are focused on navigating daily loss, trauma, and displacement, technical concepts like "climate action" feel utterly distant and irrelevant. Traditional, top-down communication strategies fail because they rely on dense, jargon-filled reports that impose a high cognitive load and simply do not resonate at the local level. Research confirms this failure, showing that this "deficit-model" messaging the idea that people just need more facts only serves to increase confusion and often breeds suspicion rather than providing clarity [4]. As a result, critical environmental issues, despite their direct impact on stability and survival, become dangerously misunderstood, ignored, or even co-opted by conflict narratives.

Why Science Communication Matters in Climate and Conflict

The relationship between global climate instability and human conflict is a dangerous reality. Extensive international research shows that climate crises and conflict reinforce one another [5], creating a downward spiral of instability. In Sudan, this cycle is tragically evident, nowhere more so than in the Darfur conflict. Comprehensive historical analyses, such as the seminal 2007 report by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), explicitly concluded that environmental degradation and resource scarcity were fundamental underlying causes of the crisis [6]. Driven by decades of erratic rainfall, desertification, and climate change, competition over diminishing grazing land and water access intensified long-standing tensions between pastoralist and agricultural communities, fueling violence.

Effective science communication is the critical tool needed to break this cycle. By helping communities accurately understand their climate risks, identify localized solutions, and actively counter misinformation, communication empowers people. When communities fully grasp the true, environmental drivers of stress, they become better equipped to advocate for sustainable change, adapt to new realities, and ultimately build peace.

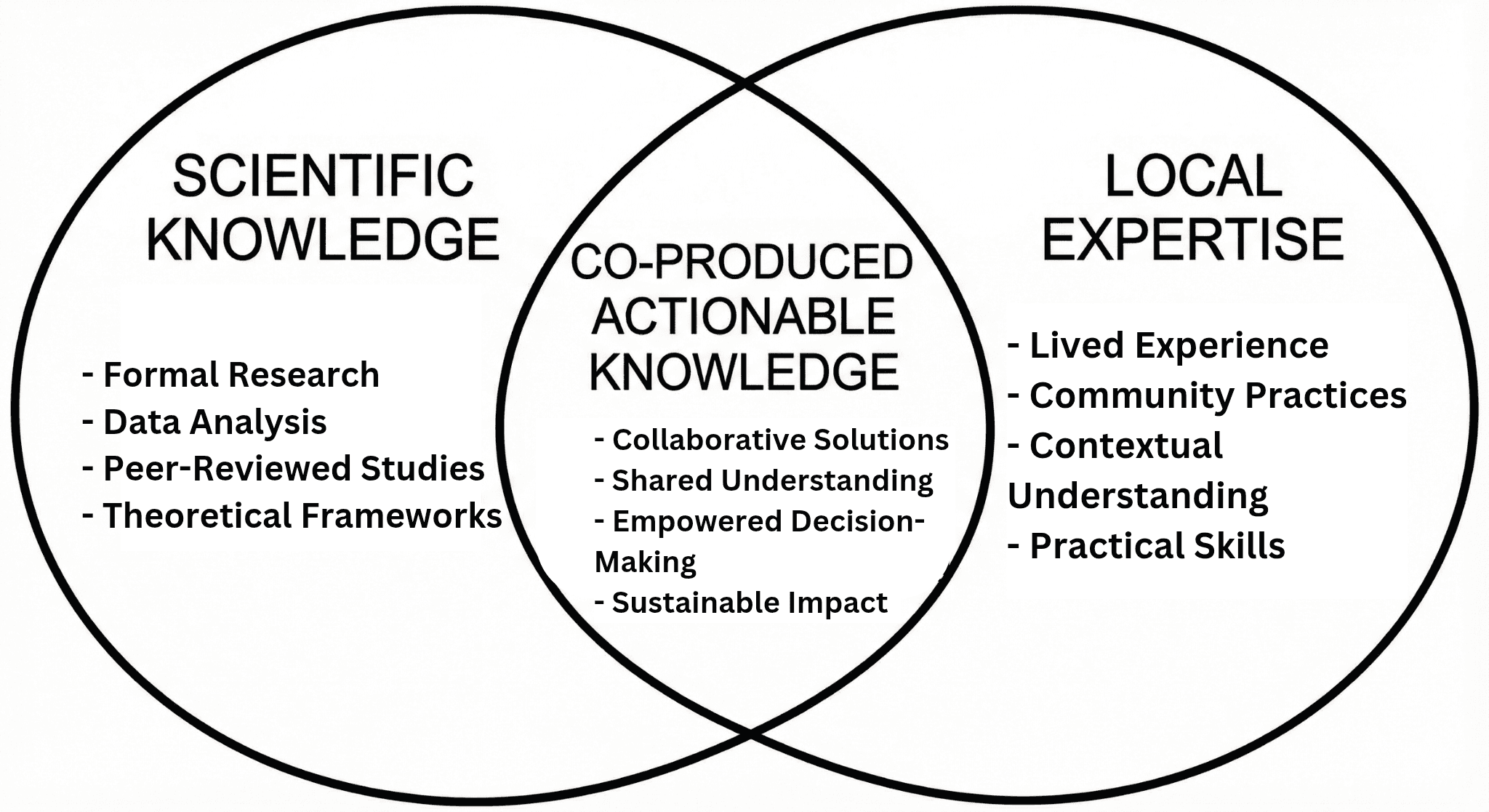

Knowledge Co-Production: Centering Local Expertise

A critical shift required in science communication is embracing knowledge co-production [7]. This method fundamentally values community experience as equal to scientific evidence. Instead of delivering information from the outside, it establishes a framework where shared understanding is built iteratively through dialogue, lived stories, and cultural insights. In Sudan’s conflict-affected regions, this approach is vital because it restores dignity to displaced communities and highlights their inherent expertise in navigating localized environmental change, such as recognising specific seasonal weather patterns or identifying resilient local crop varieties. For successful environmental adaptation, every voice is essential, making the detailed perspectives of women, youth, and elders crucial for enriching the collective knowledge base and ensuring solutions are culturally appropriate and practically viable.

Cultural Storytelling as a Bridge to Knowledge

In Sudan, traditional storytelling is far more than entertainment; as it is a core cultural practice that shapes collective memory, identity, and values. Elders pass down critical local knowledge and histories of resilience through narratives that are trusted and deeply resonant. Research in risk and science communication confirms the power of this method: storytelling fundamentally improves comprehension of scientific concepts [8]. Psychologically, narrative promotes "transportation," allowing audiences to set aside skepticism and integrate the facts within the emotionally relevant framework of the story. This is particularly effective in settings with low formal literacy. By linking climate action and environmental science to these familiar cultural forms, we can translate complex, technical ideas into accessible, trusted, and emotionally relevant information [9]. This creates a knowledge base that communities will actually use to respond and adapt, making the science memorable and actionable.

Environmental Peacebuilding: Reducing Conflict Through Information

Ultimately, the goal of the knowledge co-production approach in a conflict-affected context is environmental peacebuilding, a strategy that utilizes shared natural resources and environmental issues to foster cooperation and stability between groups. The Environmental Peacebuilding Association, along with similar organizations, consistently highlights the crucial role that trusted, actionable information plays in reducing conflict triggers. In Sudan, where communities frequently rely on rumors or incomplete data regarding critical climate and land use issues, clear and verified communication is essential for reducing fear and countering misinformation. By training local youth to communicate verified environmental data using simple, accessible language and community-rooted methods (like storytelling), environmental peacebuilding transforms from a theory into a tangible tool for post-conflict recovery and resilience through joint stewardship of shared resources.

Operational Realities: What Makes This Work Hard

Science communication in conflict zones like Sudan faces a daunting array of structural challenges. These include severe internet and electricity instability, which cripples digital outreach and prevents essential follow-up. Compounding this, the widespread trauma and displacement caused by the conflict significantly reduce the capacity of communities to focus on long-term environmental issues [10]. Furthermore, the existence of dozens of distinct local dialects requires communication strategies to be more culturally specific and adaptable. These difficulties are magnified by the rapid spread of misinformation on social media during periods of intense fighting, while local grassroots initiatives attempting to bridge these gaps struggle with severe funding deficits. Collectively, these pervasive barriers clearly demonstrate why accessible and community-driven communication is not just helpful, but absolutely essential for stability and recovery.

A Grassroots Example: Lessons from Green For Sudan

My work with Green For Sudan began as a grassroots experiment and evolved into a youth-led knowledge co-production model. Through Stories to Tell, we aim to document women’s narratives of resilience, showing how climate and conflict shape daily life. In parallel, we created Fatima, a fictional character who acts as our Climate Fact-Checker and storyteller. Inspired by Sudanese cultural heritage and stories passed down from grandparents to grandchildren, Fatima helps us connect local traditions with climate knowledge. By linking culture with climate action, Fatima makes complex environmental science accessible, engaging, and relevant for children, youth, and adults alike. Our community simulations of UNFCCC COP negotiations further allow Sudanese youth, especially the displaced, to practice policy thinking and develop global awareness, fostering critical thinking. The aim is to explore the country’s climate, environmental, and sustainability challenges through the lens of negotiation, diplomacy, and evidence-based decision-making. This builds confidence, improves critical thinking, and helps them see that their voices and insights are relevant to global climate conversations. Demonstrating that when young people understand the science behind their environment, they become confident leaders and peacebuilders.

Conclusion: A Path Toward Environmental Understanding and Peace

Sudan’s crises are complex, but one truth stands out: communication is a form of recovery. When science is translated through culture, storytelling, and local experience, it empowers communities. A single water initiative can rebuild trust. A shared narrative about resilience can unite divided groups. Science communication may not end conflict, but it provides the clarity communities need to make informed decisions and move toward peace. Sudan’s future depends on youth who understand both the environment and their responsibility to protect it. By blending science with storytelling, we plant seeds of resilience, one conversation, one community, one story at a time.

References

The environmental costs of the war in Sudan - CEOBS [Internet]. CEOBS. 2025. Available from: https://ceobs.org/the-environmental-costs-of-the-war-in-sudan/

Soliman A, Baldo S. Research Paper Gold and the war in Sudan [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/2025-03-25-gold-and-the-war-in-sudan-soliman-and-baldo.pdf

War-Torn I. In War-Torn Sudan, a Gold Mining Boom Takes a Human Toll [Internet]. Yale e360. 2025. Available from: https://e360.yale.edu/features/sudan-war-gold-mining

Grant WJ. The Knowledge Deficit Model and Science Communication. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Nov 28]. Available from: https://oxfordre.com/communication/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-1396?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190228613.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190228613-e-1396&p=emailAqgLqn3rNkcmw#:~:text=Among%20science%20communication%20researchers%20and,challenge%20in%20science%20communication%20research. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1396

Scheffran J, Brzoska M, Kominek J, Link PM, Schilling J. Climate Change and Violent Conflict. Science [Internet]. 2012 May 17 [cited 2019 Feb 27];336(6083):869–71. Available from: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/336/6083/869.full

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Sudan Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment. Nairobi: UNEP; 2007. Available from: https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/api/core/bitstreams/31cb26ef-2e97-45c8-983d-53c6f9143a81/content

Norström AV, Cvitanovic C, Löf MF, West S, Wyborn C, Balvanera P, et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nature Sustainability [Internet]. 2020 Mar 1 [cited 2020 Oct 19];3(3):182–90. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-019-0448-2

Dahlstrom MF. Using Narratives and Storytelling to Communicate Science with Nonexpert Audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 Sep 15;111(Supplement 4):13614–20.

Adger WN, Barnett J, Brown K, Marshall N, O’Brien K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change. 2012 Nov 11;3(2):112–7.

Khalil KA, Mohammed, Balla A, Alrawa SS, Hager Elawad, Almahal AA, et al. War-related trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees, displaced, and nondisplaced people during armed conflict in Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Conflict and Health. 2024 Nov 1;18(1).